FERAL CAT CONTROL

Lotek collars that are fitted to feral cats to track their movements around Artemis Station.

In recent years, there has been a lot of attention paid to managing the impacts of Feral Cats on Golden-shouldered Parrots (GSPs). Despite there being only a small number of cases of verified cat predation, GSPs have some traits associated with other birds that frequently fall prey to cats; they feed and nest on (or near) the ground, they are small and occur in open habitats.

FERAL CATS ARE A THREAT

Since October 2019 we’ve removed 51 Feral Cats from within and around GSP habitat on Artemis. Taking into account the relatively limited “search” or “trap” effort required to remove this number, we can conclude that cats occur at high densities on Artemis. For example, in July 2023 we trapped 8 cats in only 3 nights (using 10-13 traps).

So when all this is considered – the high Feral Cat density and likelihood of GSP predation – we treat Feral Cats as a potentially serious threat to GSPs on Artemis.

Teghan D. Collingwood et al (2020): Native and exotic nest predators of Alwal (Golden-shouldered parrot Psephotellus chrysopterygius) on Olkola Country, Cape York Peninsula, Australia, Emu - Austral Ornithology, DOI: 10.1080/01584197.2020.1750963

Woinarski et al. (2017): Compilation and traits of Australian bird species killed by cats, Biological Conservation

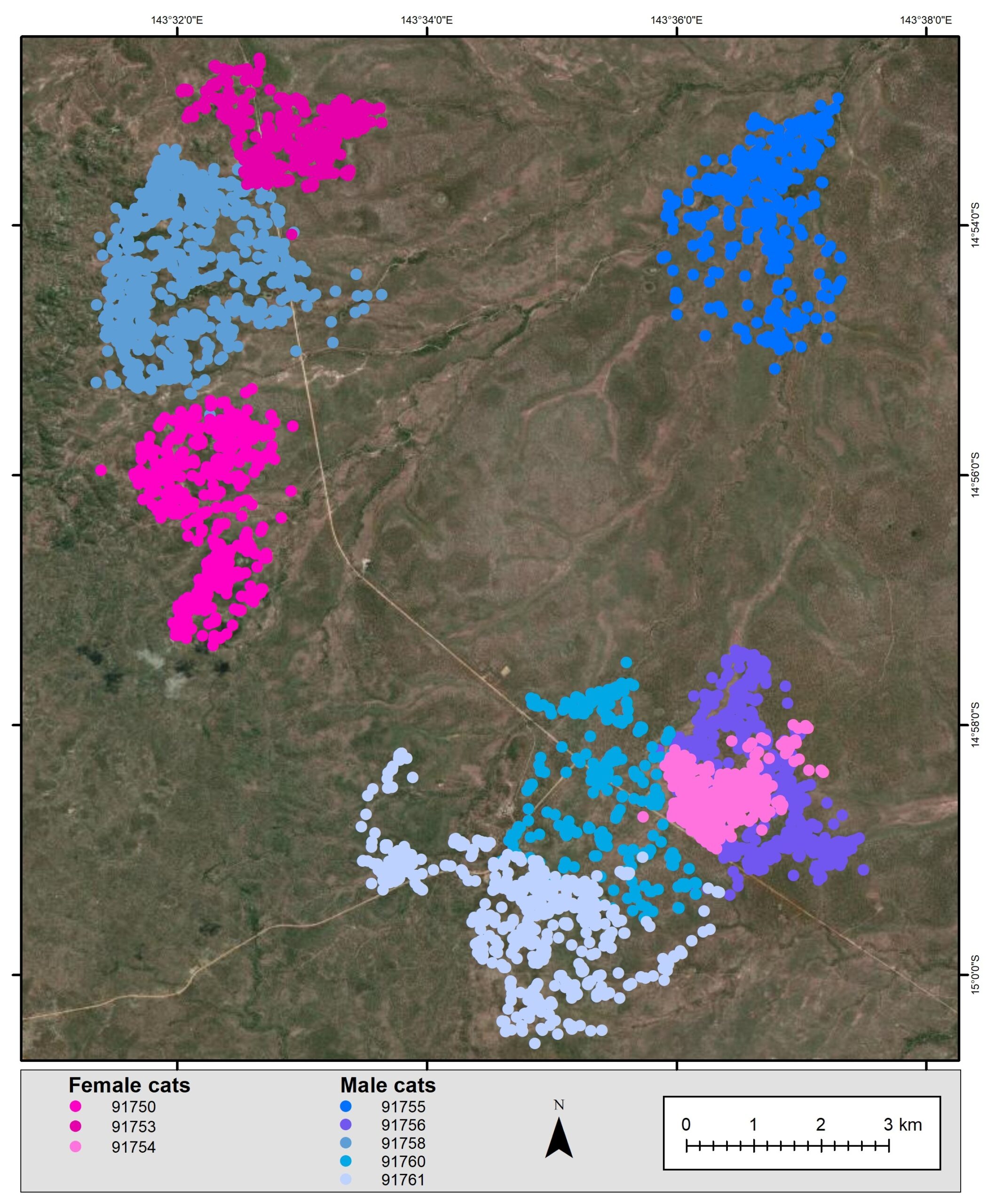

Tracking map of eight tracked feral cats in October 2020 at Artemis Station.

A Felixer trap set up and ready for use on Artemis.

ARE WE MAKING THE CAT PROBLEM WORSE?

One of the things we worry about is doing things that inadvertently makes life easier for Feral Cats. For instance, reversing woody thickening often results in the accumulation of fallen timber, branches and leaves. Depending on the location and habitat, we also create edges between the grasslands and adjacent woodlands. Early dry season and storm burning are also important tools we use for habitat restoration and management. All of these things could potentially attract Feral Cats.

To investigate the likelihood of this occurring, in 2020 and 2021 we captured 8 Feral Cats and released them with GPS tracking collars. We did this to see if Feral Cats were attracted to the areas we had restored. We also wanted to learn more about how Feral Cats use the Artemis landscape to inform our Feral Cat management actions.

THE ANSWER IS "NO, BUT..."

Three tracked Feral Cats had home ranges that encompassed habitat restoration areas and a fourth cat’s home range was within 100m of one of the restoration areas. Of these four cats, only two visited restoration areas after clearing had taken place. And even then, they did not spend an unusually large amount of time there. Furthermore, none of the cats were attracted to the fires we had lit as part of our habitat management program. So based on all these results, we concluded that Feral Cats were not strongly attracted by our actions which means that there is no urgent need to immediately integrate Feral Cat control into our habitat management plan.

Having said that, we are certainly not relaxing when it comes to mitigating the impacts on Feral Cats. Not only are they a risk to GSPs, but our recent fauna surveys on Artemis have discovered several threatened, or range restricted species, that have high conservation value and we know are impacted by cats. Included in these are Coen Rock-wallabies, Spectacled Hare-wallabies, Black-footed Tree-rats and Northern Brown-bandicoots. Given these values, Feral Cat control is a high priority for us at Artemis, and we’re constantly working on refining our actions.

KNOW THY ENEMY...

Some of the interesting things we did learn from the GPS tracking were that the “core” home ranges of male cats (i.e. where they spend most of their time) were not significantly larger than for females.

However, when we looked at the overall home ranges (i.e. all of the places they visited), males’ home ranges were significantly larger than for females (579 hectares versus 294 hectares). GPS tracking also taught us a lot about how Feral Cats move through the landscape, and that Feral Cats rarely hunt during the day during warm weather (about 5% of daytime movements were greater than 200m).

We are planning to do some more cat tracking in the winter months to see if diurnal hunting increases, which could increase risk to parrots. All this information now helps us when it comes to designing our control program.

A HIGH-TECH BOOST TO OUR CAT CONTROL EFFORTS

A further boost to our Feral Cat control program came in 2022 when we received funding from Queensland Government to trial the use of Felixer traps . These high tech devices use lasers and Artificial Intelligence to discriminate Feral Cats from non-target species and then deliver a lethal dose of poison to their fur, which they ingest by grooming.

Whenever Felixers are used for the first time in an area, a requirement of use is to operate them in “photo only” mode for two weeks to ensure no non-target species are incorrectly assigned as Feral Cats. We did this early in 2023 and all three Felixers passed the test with 100% accuracy. Since arming them, we have now removed 6 Feral Cats from inside critical GSP habitat.

IT'S ALL ABOUT PRESSURE

Feral Cats are a significant threat to GSPs and other wildlife on Artemis. They are also incredibly challenging to control, and we cannot realistically expect to eradicate them. The best we can hope for is putting some downward pressure on the population, which we’re doing. 51 less Feral Cats from core GSP habitat must be a good thing, even if we only temporarily reduce predation risk to our precious wildlife.

Camera trap photos of a feral cat on Artemis Station.