SAVING GOLDEN-SHOULDERED PARROTS

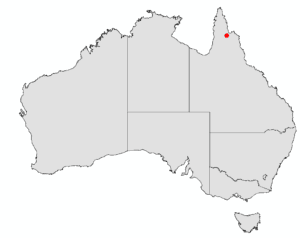

Golden-shouldered PARROTS (GSPs) have disappeared from more than half of their range since the 1920s. There are estimated to be as few as 770 individuals left in the wild.

Artemis Station, on Queensland's Cape York Peninsula, was once a stronghold for GSPs. However, the population has crashed to about 50 birds over the past 10 years. All the evidence suggests Artemis’ parrots will disappear completely if we don’t act now.

There have been dramatic changes in GSP habitats on Artemis over the past 50 years. In particular, small trees and shrubs have invaded grasslands and open woodlands. This has allowed parrot predators to increase in number and also benefited their ambush hunting tactics.

Crowley GM, Garnett ST (2023). Distribution and decline of the Golden-shouldered Parrot Psephotellus chrysopterygius 1845–1990. North Queensland Naturalist. 53:22-68.

Garnett ST and Baker G (2021). ‘The action plan for Australian birds 2020’. (CSIRO publishing, Melbourne)

The same location on Artemis 20 years apart. The natural grassland has been invaded by shrubs, in this case, Melaleuca citrolens

Antbed nest protected by electric barrier fencing.

Monitor attacking GSP in their unprotected nest.

OUR APPROACH

In order to save GSPs on Artemis we have two broad strategies: (1) secure the remaining birds using interim interventions, and (2) restore habitats which will provide long-term population security.

We are closely monitoring our actions in various ways including measuring nest outcomes and the survival of individual parrots.

INTERIM INTERVENTIONS

It's a risky strategy to rely solely on habitat restoration to reverse the decline on GSP's on Artemis. Restoring a significant amount of GSP habitat may take another 5-10 years.

During this time, the population may dwindle to such low numbers that recovery is impossible. So we need to secure and grow the remaining GSP population now.

There are 3 levers we can pull to secure and grow the population. The first involves protecting nests from predators to increase the number of baby parrots that fledge. This is done using a combination of electric barrier fencing and meat ant control (which can be a significant cause of nestling mortality). Second, we are ensuring that once they leave the nest, juvenile and adult parrots are safe from predators such as Feral Cats. Third, we are providing supplementary food in predator-safe structures to help parrots through periods of food shortage.

It boils down to survival: we are doing whatever it takes to increase the lifespan of GSPs. To make sure we’re doing the right things in the right way, we are following the fate of individuals using colour-banding.

This GSP has coloured bands on its legs to assist in identification.

HABITAT RESTORATION

The process that has caused the GSP population to crash is high levels of predation, which is being driven by an increase in tree and shrub density. Basically, there are now more predators that are killing parrots more effectively. Parrots simply cannot see the predators in time to escape.

The long-term stable strategy to solve this problem is to restore parrot habitats back to an open structure, which we have been doing since 2019. But it is a painstakingly slow process. It needs to be done sensitively so we don't damage termite mounds (parrot nests) and create soil erosion problems. But we are making progress. Between 2019 and 2023 we have restored 60 hectares of critical nesting habitat. Butcherbird monitoring shows that this is reducing predation pressure.

MONITORING IS KEY TO SUCCESS

In 2023 we saw large flocks (30+) juvenile parrots darting through Artemis. This is the largest size we have seen for several years.

Through the combined effects of our habitat restoration and predator control, we are expecting a greater proportion of these juveniles to "recruit" into the adult population where they should live longer. We are monitoring this using colour-banding.

Parrots are caught in mist-nets and fitted with unique combinations of coloured leg bands. This is a standard practice in ornithology and aviculture, and is a highly regulated activity requiring several permits and a licence.

Following banding, we use automatic cameras at supplementary feeding stations to check who's coming and going. This is providing us with information about individual survival. Such information makes sure that we are pulling the right levers in trying to restore GSPs on Artemis.